IBA as a format

The International Building Exhibition as a format

International Building Exhibitions (IBAs) have been around for more than a hundred years.

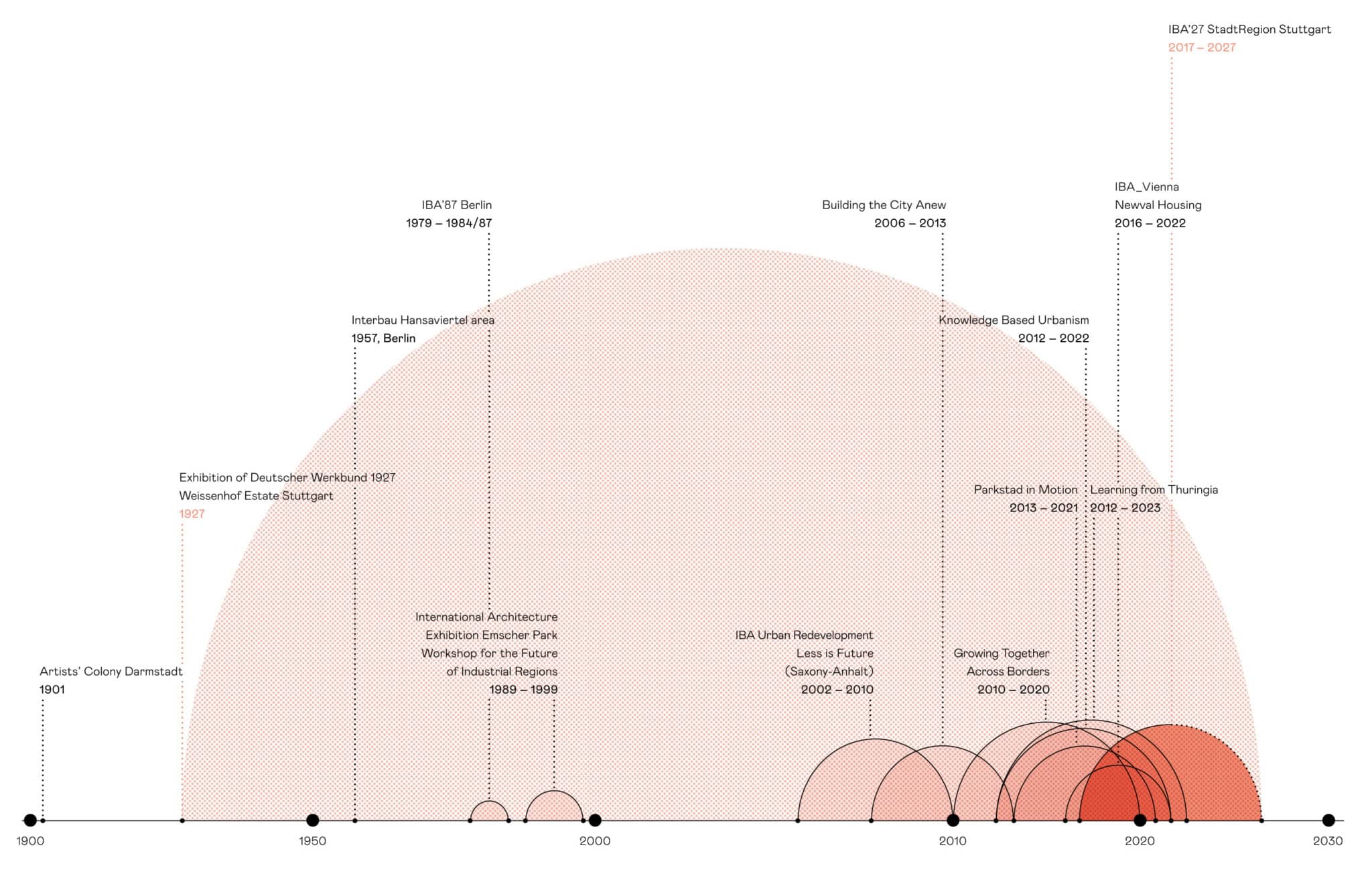

Inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement in England, an artists’ colony sprang up in Darmstadt’s Mathildenhöhe at the turn of the 20th century that took a critical approach to all areas of life and endeavoured to reorganise them. The results were presented in an exhibition held in 1901. This prime example of German Jugendstil is now viewed as the first building exhibition.

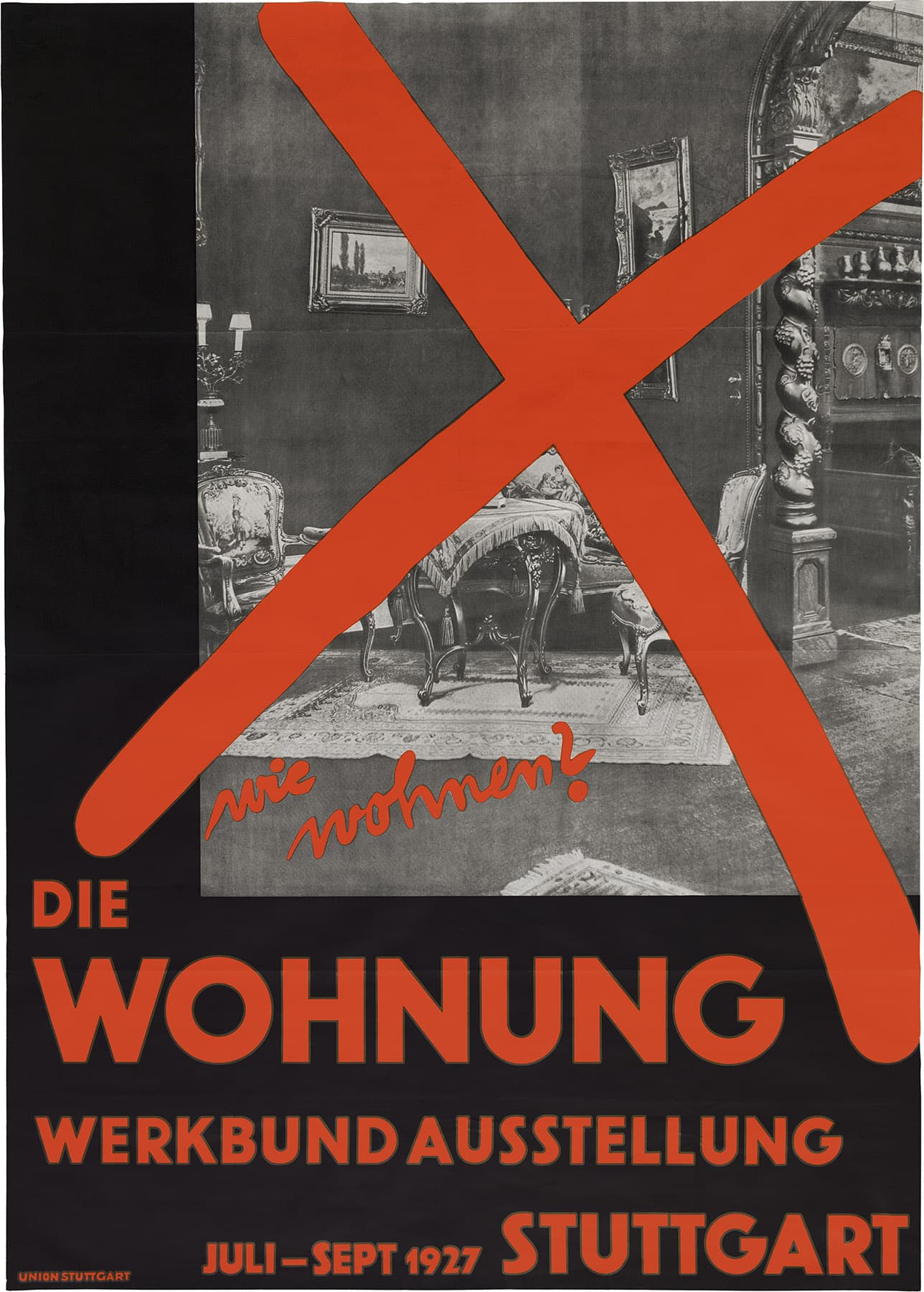

In the 1920s and 1930s, no fewer than six building exhibitions across Europe initiated by Deutscher Werkbund (the German Association of Craftsmen) demonstrated the triumph of Modernism by bringing together industrial production forms, radically new design and new forms of housing.

The first and probably most spectacular Werkbund exhibition, »Die Wohnung« (The Dwelling), took place in 1927 in Stuttgart: In addition to the Weissenhof Estate with its 21 model buildings, it presented modern design, contemporary materials and state-of-the-art technology to half a million visitors at a trade fair site in Stuttgart’s city centre.

The 1957 »Interbau« in the Hansaviertel area of Berlin reflected post-war Germany’s attempt to connect with Modernism. The principles showcased there dominated urban planning for the decades to come, with large-scale housing developments and a strict separation of functions.

In 1987, IBA Berlin explored the theme of the fractures created by those very planning principles. It looked at urban repair and a post-modern conservation of existing urban structures, while also experimenting with new forms of housing and types of buildings. While that IBA met with huge opposition at the time, today it marks the moment when building exhibitions transformed into a tool for reflective debate on the future of urban spaces.

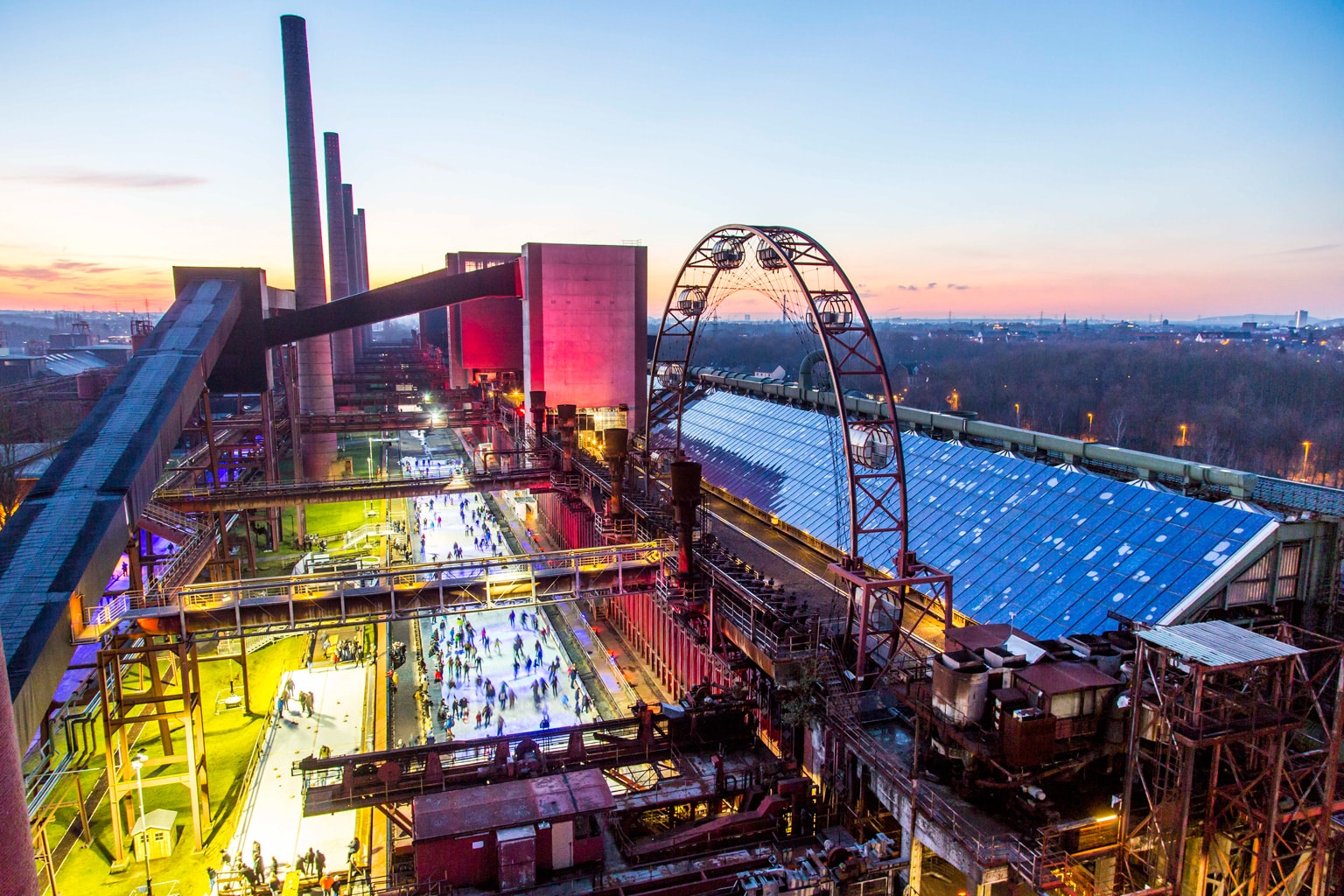

With exhibitions such as IBA Emscher Park in the Ruhr region in the 1990s, the format became an instrument for redesigning entire regions, integrated in broad-based public discourse about the future of cities.

In 2013, IBA Hamburg presented its results; it used the example of the Wilhelmsburg part of the city to look at open communities in cities, at transitional spaces between the conurbations and their surrounding areas and at cities under the influence of climate change.

Currently there are IBAs in Basel (where Germany, France and Switzerland meet), in Heidelberg, in the south of the Netherlands (IBA Parkstad), in Vienna and in the German State of Thuringia. These IBAs will conclude between 2020 and 2023.

Nowadays, building exhibitions are more than just architectural exhibitions. Instead, they are diverse large-scale projects and laboratories for urban and regional development. They change the buildings and structural fabric of cities and regions and search for daring, radically new answers to social, economic and ecological questions relating to building. Their aim is to connect the potential to be found in communities, in companies, in science and in politics in order to reconceptualise and try out the future of cities and regions.

Present-day IBAs normally run for ten years. They end with the presentation year, when the results are presented to the global public: buildings, neighbourhoods and infrastructure projects, but also innovative planning instruments and social, cultural and ecological projects. Projects realised to serve as an example endeavour to have an impact that lasts for decades.

International Building Exhibitions have no prescribed format. There is no jury that decides how they should be organised and no binding rules. At the same time, the German government has convened a panel of experts that drew up recommendations and quality criteria for the implementation of an IBA. The experts use these guidelines to support and advise ongoing IBAs.