Essay

The City of the Future is built

In medieval cities, it was the absolute right of the ruling class that put limitations on private property. Cities emerged as the manifestation of God’s plan on Earth. This link was severed by the French Revolution. The Civil Code of 1804 secured the right to property, with undivided ownership of land considered private property[1]. Consequently, the main task of planning was to develop infrastructure around private property and to enclose it with road and flight line maps.

On the fringes of Modernism

Industrial cities developed without any plan. The urban planning visions of the 20th century remained fragments or utopian designs. One example was Le Corbusier’s delusional depiction of a new Paris, Plan Voisin from 1925, which showed a city centre without any spatial links to its surroundings. Mass-constructed residential settlements were to emerge there soon after, as ideal yet autistic settlements. One noteworthy exception was the very determined Tony Garnier, who in 1918 presented his Cité industrielle as the ideal city after almost 20 years of preparation[2]. In the industrial age, planned cities tended to emerge mostly at extractive locations, like the mines in Siberia and Sardinia or the huge dams on the Dnieper River. For ideological reasons alone, however, they hardly serve as model cities for democratic societies.

Alongside criticism of these large-scale modernist projects and of the transport infrastructure for car-friendly cities – all of these Fordist, deconstructivist technical responses for a post-war society believing in growth – grew criticism of the spirit and manner in which they were implemented. »Planning« as a concept fell into disrepute. Even more important than the criticism of the methods was the failure of the planning tools to control the development of settlements from the 1970s onward. A process of global urbanisation that has resulted in over half the world’s population living in cities today was mainly comprised of growth on the fringes, combined with a fall in structural and social density in urban settings.

It is on these fringes that the future of the city will be decided. Will we be able to transform inhospitable business parks, monofunctional residential settlements and endless single-family homes into functioning neighbourhoods with a local economy for a post fossil fuel Modernist era? This is about space, about urban networks, metropolitan regions and a holistic view of the city region, the agglomeration, the »Zwischenstadt«, those unloved and unplanned places of urban architecture.

Beyond the urban and the rural

With its publication Switzerland. An Urban Portrait [3], ETH Studio Basel expanded this view to the whole of Switzerland in 2005, describing it as a city with neighbourhoods where highly productive centres are closely connected to rural relaxation destinations – resorts – and the deserted, ecologically valuable periphery – the alpine fallow lands. It was a provocation that broadened the urbanistic view but had scarcely any institutional or political consequences.

In terms of methodology and content, the same approach is taken by IBA’27 when it draws a picture of the Stuttgart Region. Here, there is neither the urban nor the rural. There are only agglomerations with different qualities and in particular differing potential. Planning for these places is impossible because the tools fall apart in federal structures and because a simple reclassification from the large to the small is not appropriate for these broadly developed structures. Good urban planning has to be about buildings, what’s inside them and the social space around them all at the same time. It’s not just a hierarchical concept that becomes more refined as it moves from the abstract to the detail.

Industrialisation shaped how people lived in this region. In Württemberg, where resources were scarce, it took advantage of water power, settling in drained areas won back from nature and building communities in the in-between spaces left over by the last land seizure. After the Second World War, small businesses and single-family homes grew up in between. The planning process simply kept track of the developments rather than initiating them. There is a clear, attractive result in terms of its geographical logic. The shopping centre at a transport hub and the expansive production facilities of global market leaders linking village centres with a collapsing identity and areas with single-family homes all tell a common story.

IBA’27 does not plan to replace these structures but to pursue a strategy of valorisation. The IBA in Berlin in 1987 recognised that Kreuzberg was built and inhabited and was defended. Consequently, alongside the »IBA New«, it created an »IBA Old«, which placed the modernist individual building in the context of a discussion about the existing housing stock. And this was exactly what made it productive in the end. IBA’27 is looking for a similar territorial compromise at regional level. Relevant topics include urban villages, productive neighbourhoods with factories and homes, agriculture that helps to adapt to climate change and is integrated into the flow of materials and energy as part of this urban space.

The Stuttgart Region has the historical genes and a present with the potential to make it a model for this transformation process. Its varied topography posed particular challenges for the people who needed to survive here. Steep terraced slopes for growing wine, fruit trees on meadows, the splitting up of land ownership and the resulting economic necessity to also learn a trade in addition to farming – all of these aspects created a small-scale cultural landscape, a rich industrial ecosystem and decentralised structures that may have changed in terms of the production methods and products but are otherwise more or less intact right through to the present day.

This landscape is full of ruptures, ill-treated by the first wave of industrialisation, the bombs of the Second World War, by people fleeing and resettling, tested in societal, multicultural processes. It has the spaces needed for its reinvention and the means to build the city of the future on this basis. The Stuttgart City Region is not unique. These types of »Zwischenstadt« emerged in many places. But this is precisely why it has the potential to become a credible example of a reinvention of existing housing stock. The thought of uniform reconstruction is not feasible here, because the splinters of history are overpowering.

Co-creation of space and community

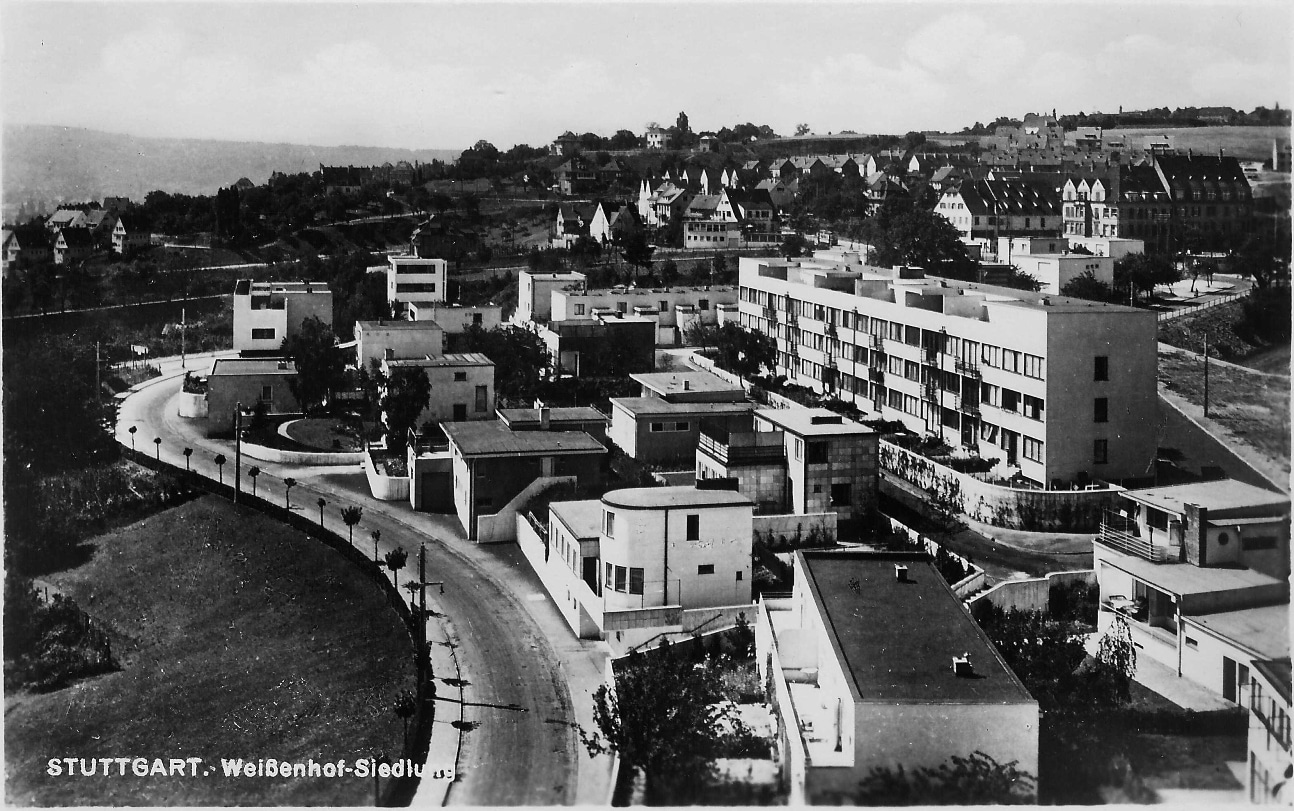

The Weissenhof Estate is the perfect example of this spatial and ideological fragmentation. It is one of the many manifestos of the turbulent last century. It is a remnant of a utopia that came under criticism and later grew into a heterogenous environment. Half of the estate was destroyed in the Second World War, with some mediocre additions made subsequently. It is a monument to Modernism, with all of its contradictions. However, it is a monument that has lost too much of its original power and is failing to fulfil the dual role of residential area and museum. This is why a strategy is needed to develop it further in a respectful way and give it a third dimension that could move the estate into the future. This could be the motto for the entire region.

Fordism compartmentalised our lives, making us accept unlived-in city centres as cultural and commercial centres. Now the current changes in retail are giving these spaces back to us. This is also true of monofunctional industrial zones and residential areas. At all of these locations, it is now possible to create more city, more community, more experimentation and more appropriation.

This transformation also puts into context the architectural disputes in the 20th century. Modernism presented itself as the only future imaginable, discrediting organic and ecological alternatives. This battle was also fought in Stuttgart between the Weissenhof Estate and the Kochenhof Estate, and this is reflected in the urban space – through technicist Modernism represented by everyone from Behnisch to Sobek and counter designs established by Bonatz and Schmitthenner and refined by Stirling and Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei. Both directions turned out to be mere rhetoric. Mies van der Rohe and Scharoun are worlds apart, while Le Corbusier created a cosmos between the Weissenhof Estate and Ronchamp that only »eyes that do not see«[4] bring together as the end of styles and of the story.

With post-Modernism having lasted 50 years and thus just as long as Modernism (1920 to 1970), it is high time to end this mock fight and face the challenges of a future that has no room for heroic new creations. Conversion culture must refashion the rich material left behind by 150 years of industrial society into a gentle, resource-saving and globally just future.

To do this, however, we must radically remove imperious and normative approaches from the creation process for urban planning and architecture and replace them with the co-creation of space and community. The aim is a process-based culture of continuing to build rather than building regulations geared to new buildings. Getting rid of top-down planning creates scope for a new design approach. This step leads to a long overdue real democratisation of building culture, without which we will not be able to master the future. Who is supposed to design the city and own the city if not the people who live in it? Land speculation and housing speculation cannot continue to threaten the diversity of the city by pushing economically disadvantaged households out of city centres. In addition to obsolete planning legislation, the renegotiation of the land issue therefore belongs on the agenda. This would initially probably take the form of a new self-awareness of the municipalities in dealing with their housing stock, building land resources and as an incentive for companies that are geared to non-profit and take a long-term view.

An IBA as a temporary exception has to show buildings. But it also has to answer the question about the conditions in which architecture is produced. In this precarious intermediate zone, the future can emerge as a non-utopian place.

[1] Hildegard Schröteler‐von Brandt: »Geschichte der Stadtplanung«, in: ARL – Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung (Hg.): Handwörterbuch der Stadt‐ und Raumentwicklung, Hannover 2018, S. 805–821, hier S. 806

[2] Vgl. Tony Garnier: Une cité industrielle – Étude pour la construction des villes, Paris 1918

[3] Roger Diener, Jacques Herzog, Marcel Meili, Pierre de Meuron, Christian Schmid und ETH Studio Basel – Institut Stadt der Gegenwart: Die Schweiz – Ein städtebauliches Portrait, Berlin/Boston 2005

[4] Le Corbusier: »Des yeux qui ne voient pas…«, in: L’Esprit Nouveau 8 (1921), S. 845 f.